This text was published by Rike Sitas, Liza Rose Cirolia and Marcela Guerrero Casas, 20 April 2021, at the website of African Centre for Cities and the African Urban Research Initiative (AURI)

The AURI workshop series concluded on 25 March with an interactive session about comparative and collaborative research. Moderated by Liza Cirolia and Rike Sitas, this workshop built on the two previous workshops on co-production and communication and focused on the value comparative studies offers to Urban Theory and practice across African cities.

Liza introduced the session by reiterating the goal of the AURI workshops to build skills among members and to expand the network. She then set the scene for this type of research in the Global South and stressed that cities in Africa are no longer just sites of, or data collectors for international research and that “individual countries can speak to global policy and global theory and practice.”

Specifically, Liza pointed to Garth Myers’ notion of African cities as “unusual suspects of comparative study” given that normally such research has been focused on large cities of the North like Paris, New York, etc. She noted that the context has not only changed, but that “this postcolonial thinking has infused global research networks, which have responded with opportunities for large research projects and collaborative work.”

The group was invited to think about establishing collaborative efforts both with colleagues across the Global South as well as funders in the Global North by introducing their own tacit and expert knowledge about what is interesting in their cities. Against the backdrop of COVID-19, Liza underscored that there will be less movement of people and more movement of ideas which necessitates building relationships and trust to move these ideas into virtual platforms and spaces.

Comparative work in context

Omar Nagati from the Cairo Lab for Urban Studies, Training and Environmental Research (CLUSTER) and Sylvia Croese from University of Wits in Johannesburg, then proceeded to give inputs. While Omar reflected on key lessons learnt in undergoing a comparison study between different cities both within Egypt and across the African continent; Sylvia spoke about the lesson and challenges of creating a comparative framework for SDG localisation.

Omar described the comparative approach his team used across the three Egyptian cities Cairo Alexandra and Minya through graphs, photographs and a short animation. They had three objectives in mind; to challenge the hard boundaries between formal and informal, to promote a more integrated city and to explore using this methodology in other cities.

The research in Egypt looked at the neighbourhood and city scales and used three parameters: borders, crossings and activities. Based on the resulting patterns, the research team generated policy questions related to municipal services, Omar explained that “by understanding what happens around these nodes, you can understand what happens in the city at large in terms of transport, economic activity, etc.).”

The “urban journey” was one of the most interesting tools developed in this project to challenge the separation of formal and informal and rather engage with the continuity of the urban experience. This same idea was used in a multi city comparison that included Cairo, Ouagadougou, Dar es Salaam and Lusaka across the themes of transport, housing, water and food respectively.

Comparative work in action

The second input focused on how different cities worked to localise the New Urban Agenda and the practicalities of working across various cities with different contexts, but all grappling with the same global question. Sylvia summarised the work the Mistra Urban Futures network carried out across seven cities, how the comparative study was initiated and the various challenges and positive experiences along the way.

Sylvia reflected on the great diversity involved in this study. Cities not only ranged in size, from the big metro Buenos Aires, Argentina to the small town of Shimla in India, but also exemplified various governance structures and approaches. For instance, while Kenya was very top down, Cape Town used a bottom up approach, and each city had different levels of political interests and leadership as well as different set ups in terms of the existing research collaboration set up. In all cases, it seemed “data on few or almost none of the SDG indicators were readily available or relevant to those cities.”

Sylvia reflected on the practicalities of carrying out such large-scale research and attributed some of the success to working with a clear plan and deliverables, having a centralised location for all documentation, a lead researcher who managed meetings and tracked progress and working with colleagues at a similar career level, to mention only a few.

She also highlighted that one of the key findings in this comparative project was the importance of leadership or champions in local government and warned of the dangers of introducing too many agendas (New Urban Agenda, Paris Climate action, etc). She stressed the importance of integrating them with existing policies and plans and incorporating all stakeholders, including non-state actors.

Following the two presentations, participants engaged in various discussions delving into the difference between generic and generative comparison as well as comparing notes about dealing with language and cultural differences.

Participants interrogated the idea of comparison and scale and challenged the notion that it is possible in all contexts, stressing that “you can’t compare a table with an elephant” highlighting the need to select the appropriate type of research.

Warren Smit underscored that this type of research is not just about comparing places but trying to understand why things are different in different places. Omar added that “everything is comparable, depending how you choose variables”

During the practical session, small groups reflected on possible topics of comparative interest in their cities which included waste management (flows and quantity of waste), people’s everyday interactions with big infrastructure projects, spatial and territorial manifestation, and the architecture of traffic congestion.

The workshop concluded with an invitation to participants to explore opportunities for comparison and collaboration within the AURI network. Ultimately, the network seeks to strengthen this platform to encourage more interaction and collaboration across member institutions and individuals.

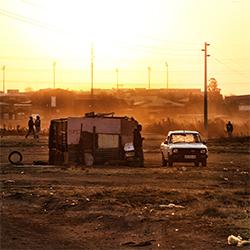

Picture: Cairo by Omar Elsharawy at unsplash.com